The Case for Residential Cafes

Why cities should let small gathering spaces exist where people live, not just where they can drive to

I went to St. Louis this week, a city known for both its urban sprawl and its dense pockets of civilization. Somewhere in between lies a neat cafe named Fiddlehead Fern. We saw some great reviews for it on Google and decided to check it out.

Nestled between lines of rowhomes and duplexes, the cafe itself was quite remarkable. The barista, immersed in her work, brewed one of the best cortados I’ve had in a while. The fresh coffee’s warm, toasted aroma energized our senses as we sat outside in the open air.

The experience was incredible, but halfway through I was struck with how quiet it was outside. It looked like the only business for at least one or two blocks and was completely surrounded by duplexes. That’s when I realized how easy it must be to walk here if you live in the surrounding community.

While the coffee was amazing, I think the idea of the cafe underscores a more crucial point: Communities need local gathering places like this.

Placemaking as a Practice

There are a number of reasons why cities should incentivize this pattern of development. For one, placemaking adds an extra dimension to existing communities, giving people more options closer to them. They add character and serve as gathering points for the locals.

Public parks, playgrounds, gardens, gyms, libraries, small shops and cafes serve as a remedy for the isolation festered by postwar urban sprawl. The lower density leads to a larger distance between homes. When there’s less to do nearby, people tend to stay at home, and the opposite is true for areas with more things to do within walking distance. It’s a well-documented phenomenon all over the world. Thriving social spaces are crucial for communities to function properly, as I detailed in a previous article about street markets. They work even better when neighbors can reach them via walking, cycling or public transit.

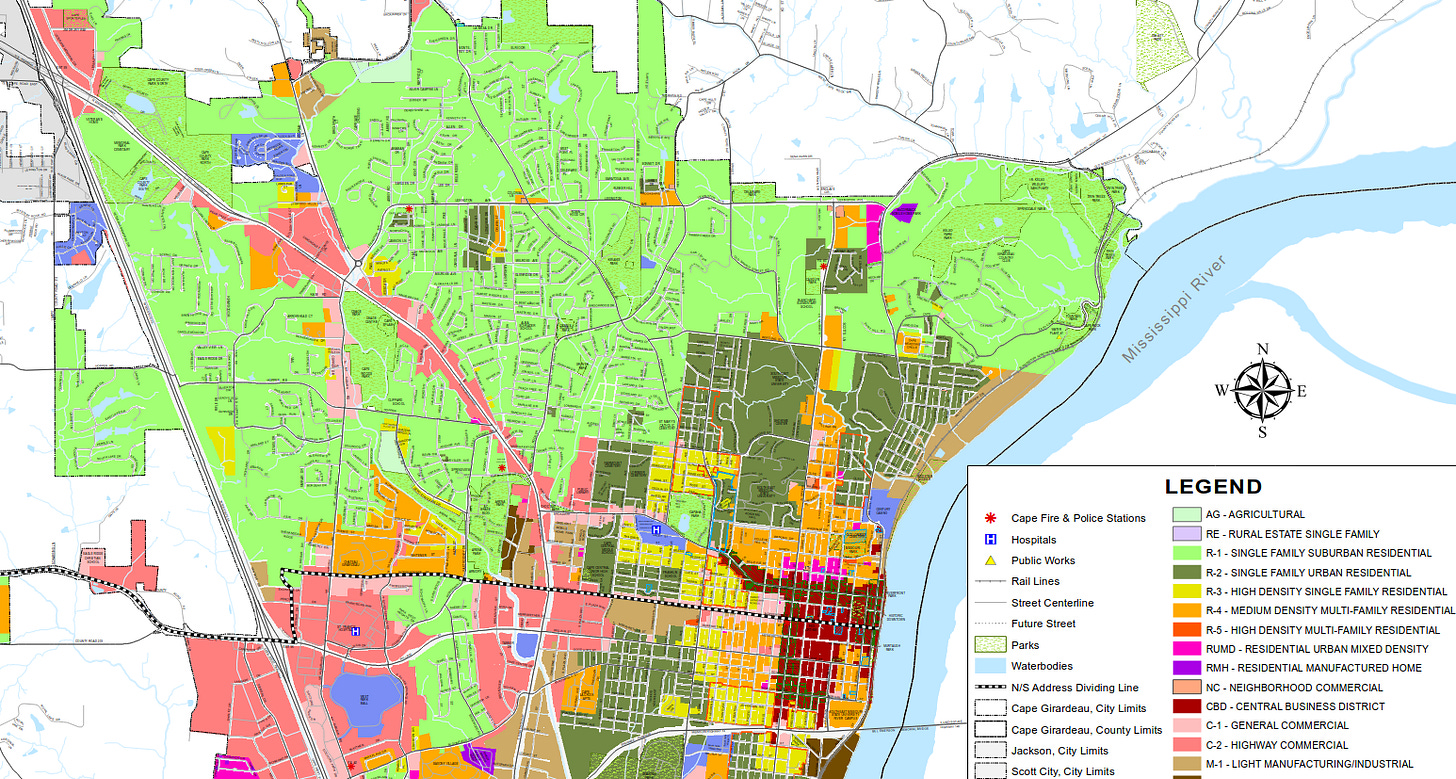

But a problem we see today is with zoning restrictions placed on residential neighborhoods. These restrictions take many forms. One common form is single-family residential, resulting in a homogeneous array of homes with zero commercial activity allowed. Take for instance the zoning code for my city, Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

In the vast light-green portion on the northern side, it would be illegal to build Fiddlehead Fern. This land houses thousands of people, and I believe Cape is missing an opportunity to dapple the area with peaceful shops, markets, parks and more amenities that serve the immediate neighborhood. Cape does have its own pockets of mixed-use residential, but most of it is concentrated by the University, and walking would take hours if you live far away. Therefore, most people simply drive downtown.

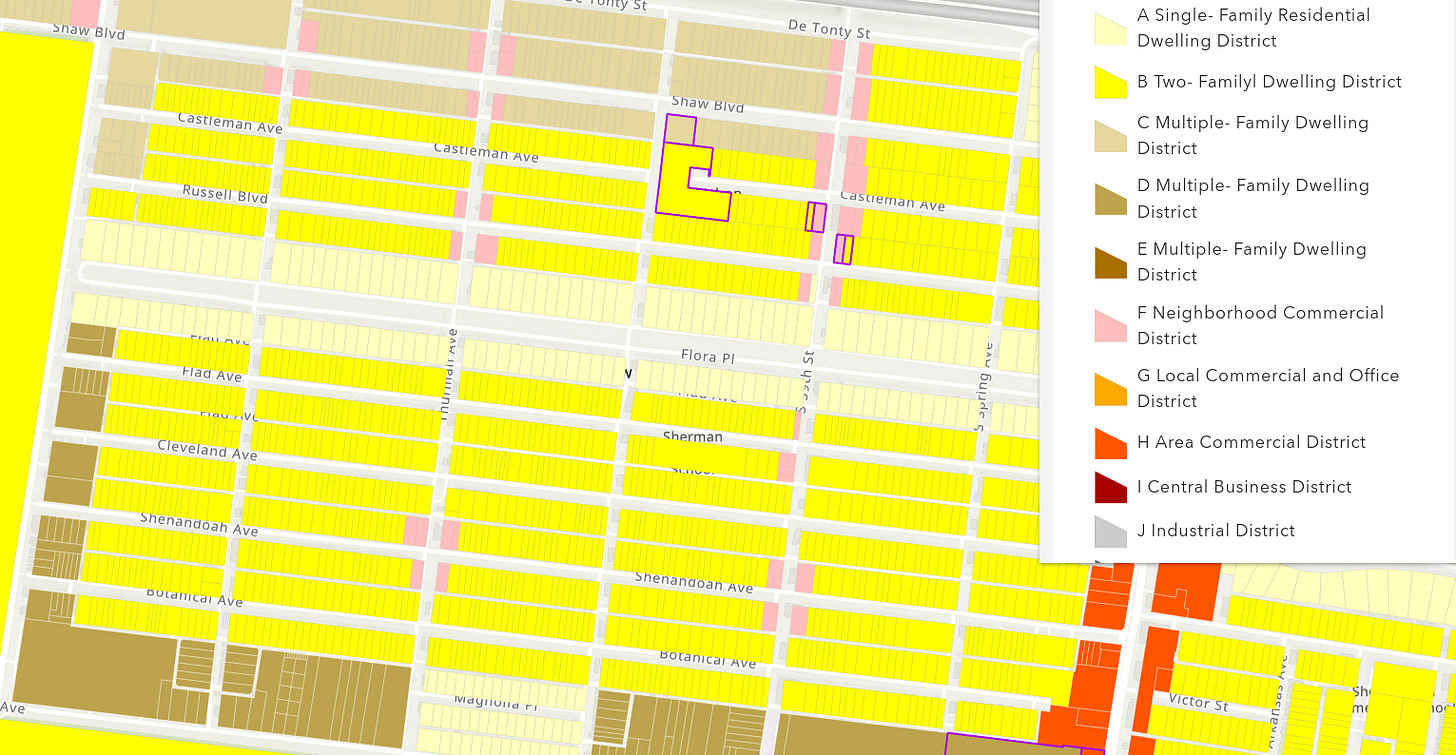

Compare this to Shaw in St. Louis where Fiddlehead Fern is located. The bright yellow portion signifies two-family residential (duplexes). The small, rosy squares are commercial zones where shops are allowed to exist. Notice how many of these small spots there are just in this one neighborhood. Nobody is farther than two blocks from a local shop. Prior to World War 2, towns all over the United States looked like this because people weren’t as dependent on cars. Shaw, for instance, has a 150-year long history that sustained this pattern of development, despite the automobile’s widespread adoption.

St. Louis does not look like this all over. Both St. Louis and Cape Girardeau have large, sprawling neighborhoods with fewer points of interest within walking distance — fewer parks, fewer playgrounds, fewer mom ‘n’ pop cafes and shops, fewer grocers, and fewer libraries. What’s left is removed far away from anyone’s home, surrounded by seas of impersonal parking spaces.

Contentious History

Consequently, suburban sprawl underscores a more sinister element with a lot of history. In the decades following World War 2, zoning restrictions further constrained mixed-use and multi-family development. As a result, thousands of single-family-zoned suburban neighborhoods across the United States were built at the expense of prominent Black and Brown communities. Much of it was because indifferent superhighways violently replaced distinguished communities.

It’s important to note this, because suburban development did not exist in a vacuum and has a long, violent history associated with it. Nevertheless, the trend is reversing, and cities are reconciling with their shameful past. In the past few decades, more and more places have begun filling in the Missing Middle. What this means is cities are offering residents more options than just single-family housing in more places, including non-detached townhomes, duplexes, triplexes, and other small apartment complexes. In reality, density doesn’t normally look like luxury highrises, which I feel is a common misconception when people think about this.

Additionally, densification solves traffic problems, because density and car dependency are inversely proportional. People have to travel farther when their neighborhood has fewer houses per square mile. Meanwhile, cities have a greater incentive to zone points of interest and build comprehensive transit systems near denser neighborhoods. They can serve more people in a smaller area and consume fewer resources in the process. Not only that, but with fewer cars on the road, the aforementioned superhighways are not needed.

Coupled with better pedestrian infrastructure, all of this means neighbors can walk or bike to local grocers, cafes, parks, and so much more without ever having to step foot in a car. They will have a common gathering place without straying too far from home, strengthening social bonds and building community in the process. More importantly, all of this can be done without the violent displacement of families from their homes.

The Gradual Remedy

I think Fiddlehead Fern is more than a charming cafe in a quiet, nondescript St. Louis neighborhood. A thriving business in a quiet residential neighborhood is evidence that this pattern of development simply works. Neighborhoods like this exist all over the United States, inviting people to live and work in shared spaces where they don’t have to travel as far to meet their needs. The social and environmental benefits to this are innumerable.

More cities are relaxing zoning restrictions across the US, allowing for more mixed-use and residential-commercial development. If you’d like to run a business that serves your immediate community, I implore you to check our your city’s zoning code. If it isn’t possible to build, consider petitioning your city council representatives and make a case using the arguments above. I for one would love to see Cape Girardeau sprinkled with its own versions of Fiddlehead Fern.

What do you think? Does your own city allow this type of zoning outside of downtown? I’d love to hear your thoughts.

I found your Substack and I searched for my city for the local genealogy meeting. This is an interesting Substack. I’ve never thought about zoning in the way you were presented it, but it makes sense.